We take a look back at the VFX pioneers behind George Lucas’ original space opera trilogy Star Wars (Episodes IV – VI) and their work with stop-motion, miniatures and motion-capture technology.

It could be said that the Star Wars trilogy, along with Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, advanced visual and practical film effects into the brave new world of filmmaking that we know today. An irony considering Lucas didn’t expect to make any further Star Wars films because he didn’t believe the technology would ever exist to make them the way he envisioned.

Talking to Wired, Lucas said “I never thought I’d do the Star Wars prequels because there was no real way I could get Yoda to fight. There was no way I could go over Coruscant, this giant city-planet. But once you had digital, there was no end to what you could do.”

The director’s vision for Star Wars (and its subsequent films) required a team of experts to turn it into a blockbuster series that is still drawing audiences forty years later.

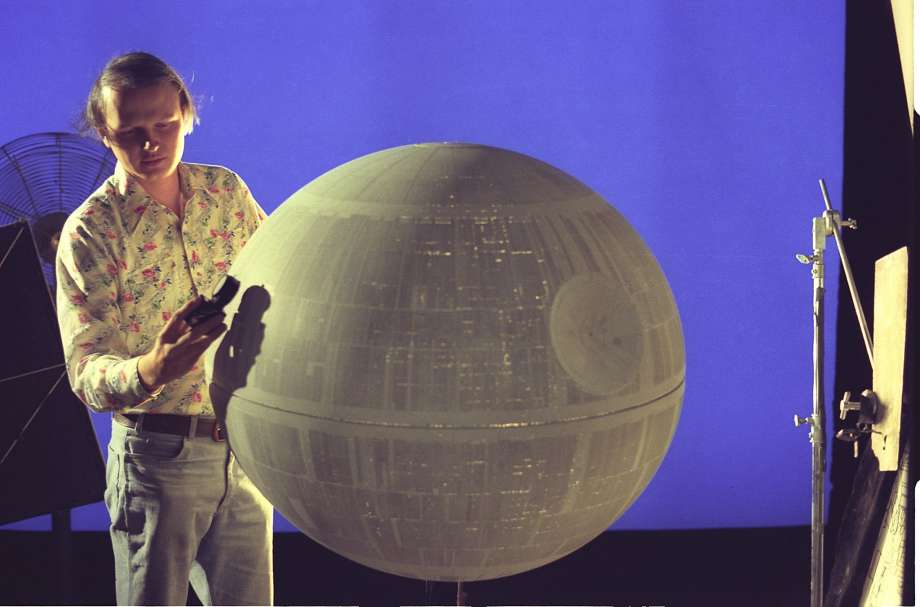

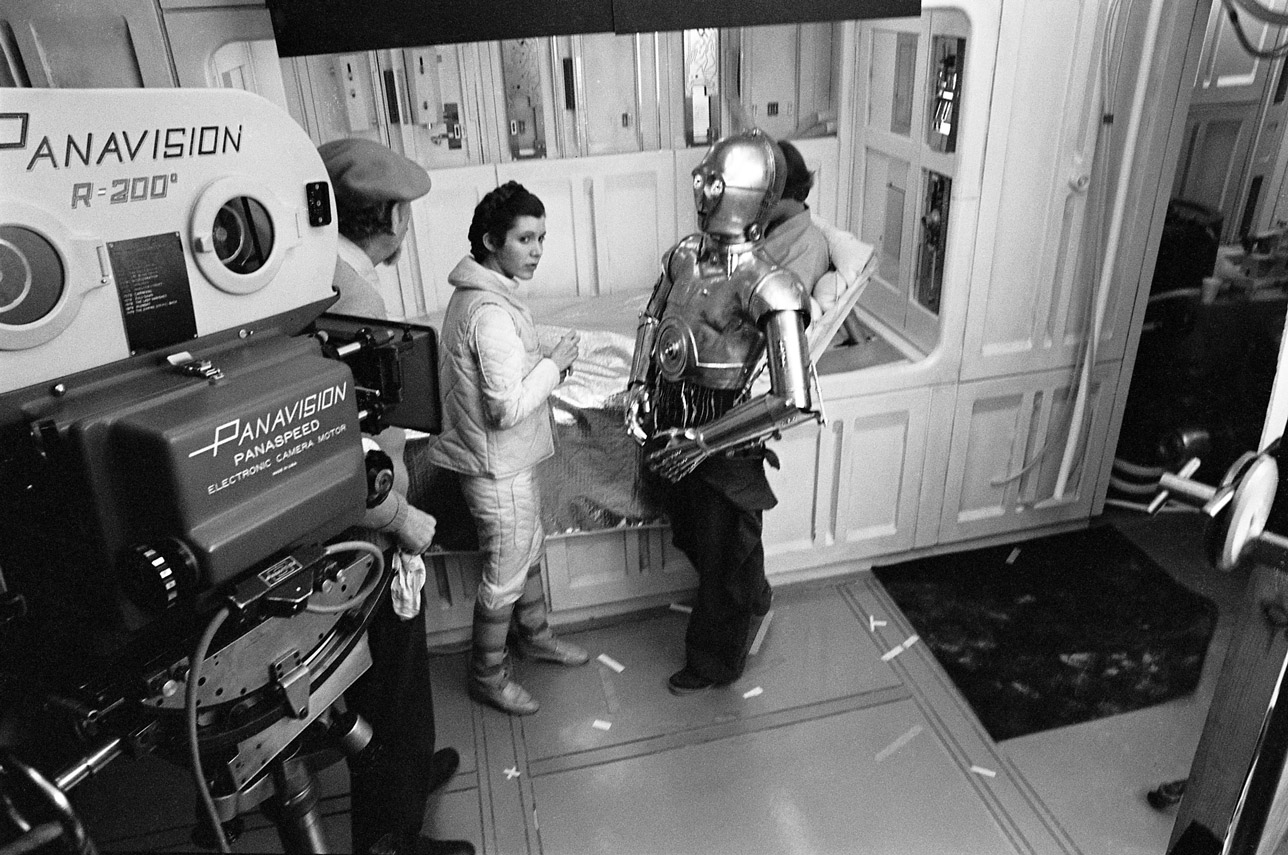

Working out of an industrial warehouse in Van Nuys, Los Angeles, Lucas gathered a team of 45 like-minded creatives, most aged in their mid- 20s, to create the effects for A New Hope.

Discussing the warehouse, model maker and VFX Artist Steve Gawley told Wired,

“There was no interior; our walls were two-by-fours, Visqueen stapled onto them. Every once in a while we’d get crazy with the music—the big record was Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours—and you’d have to turn it down because the walls were plastic.”

That early team became the backbone of Industrial Light & Magic (ILM), and included John Dykstra ASC, Richard Edlund ASC, Dennis Muren ASC, Douglas Smith and Ken Ralston, to name a few. Each now a master of VFX and winner of multiple Academy Awards, including the Best VFX Oscar for all three of the original trilogy.

“We were working on the articles of incorporation and we said, “What are we going to call this thing?” We were in an industrial park. They were building these giant Dykstraflex machines to photograph stuff, so that’s where the “Light” came from.

“In the end, I said, “Forget the Industrial and the Light—this is going to have to be Magic. Otherwise we’re doomed, making a movie nobody wants,” Lucas said.

Discussing those early days, Special Effects Artist John Dykstra said,

“I got a call from George and we met at a bungalow on the Universal lot. He wanted Star Wars to feel like it was shot with a World War II gunsight camera, to have that sense of intimacy with the action.

“The warehouse was probably 1,300 square feet and smelled like a gym locker. It was hotter than hell. If you lit a model with 6,000 watts, you could get to 130 degrees.”

He went on to say. “George was blurring the line between a student film and a studio film, and I think he wanted kindred spirits, people of like-minds, to make the film in an unconventional fashion.

“I think he wanted us to be ingenious with existing technology. He was in London shooting while we were developing what ended up being some groundbreaking technologies. We were designing and building optical printers, cameras, and miniatures; as a result, the process didn’t produce a lot of film at first. I can understand him being nervous about it; he was helming the show — and the studio was nervous. A lot of people questioned whether this machine we were creating was even feasible.” (Creative Cow).

VFX Artist Ken Ralston (current VFX Supervisor & Creative Head of Sony Pictures’ ImageWorks) recently said in an interview with the Hollywood Reporter, that he looks back on those times with great fondness,

“A lot of us were novices. The space battles in Jedi were hard … to get the flexibility in the camera movement to help tell the story. It was very difficult to put together with separate elements and make it all look as if it was part of the same image.”

Dykstra said the team came up with a slew of new filmmaking techniques in order to could get the shots to look the way Lucas wanted,

“It was an impossible number of shots for an era in which none of the equipment or the processes that were used to produce the film existed. It was overwhelming. It took almost a year just to get the camera going.”

“The scheme required that we invent, not the technology, but the process by which it was used. We moved the object and the camera during the exposure that gave our animation a verisimilitude that was indistinguishable from film of real world motion.”

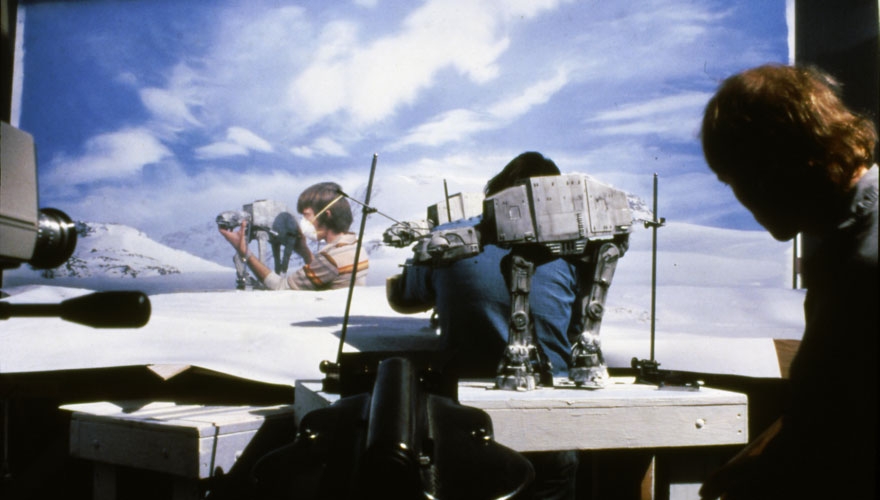

“We built a tilting lens board on the camera. We built miniatures at a scale that allowed us to have two or three stages working at the same time. To move the camera and duplicate its actions meant that we could shoot elements for six different shots on a stage in one day, because it was a modular technique

“We developed blue screen technology with high-frequency ballasts and fluorescent-lit screens instead of incandescent lights. We started building everything at the same time and it all had to work together. The miracle was that it did. I’m not sure of the dates, but I believe we went from an empty warehouse to the completion of the film in 18 months” (Creative Cow).

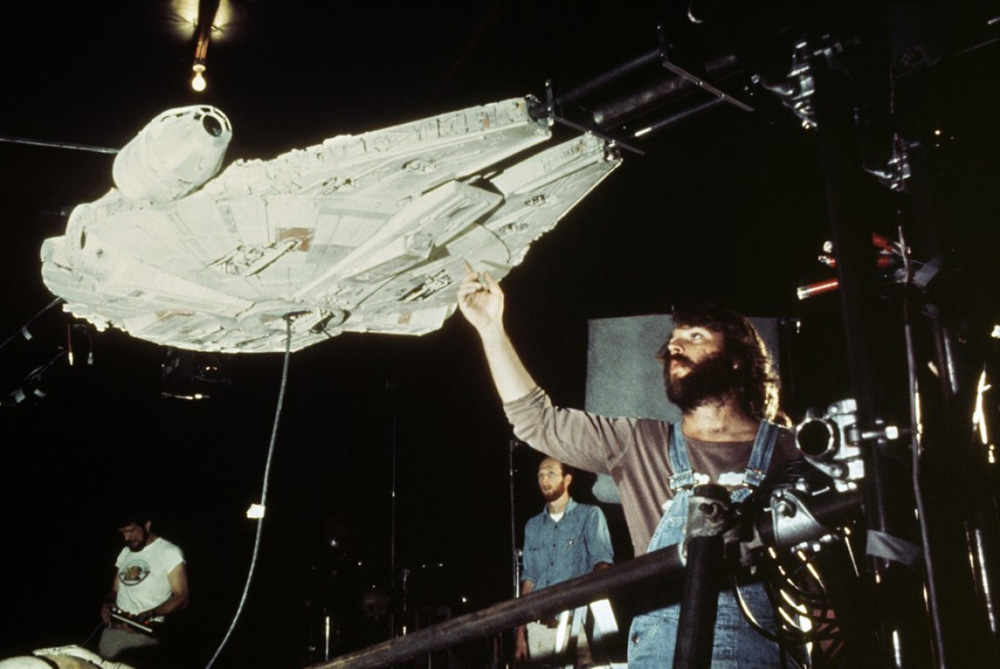

Discussing stop-motion and the creation of these new techniques, Richard Edlund told Galactic.tv,

Discussing stop-motion and the creation of these new techniques, Richard Edlund told Galactic.tv,

“When you have a fast motion of objects, you’ll have to mimic what happens with an actual 24 frame/second movie camera. That’s what you call motion blur and when the motion blur isn’t there, the image shutters and it doesn’t look natural. You can see that in the Ray Harryhausen stop-motion movies [Jason & theArgonauts, Clash of the Titans]. When you see bird’s wings and they don’t shutter, they don’t fly languidly.

So we agreed that the system would shoot on the fly and we weren’t doing a moving shoot kind of technique. John wanted to do his front light – back light technique, so you shoot one pass where you light a white card behind the model, then you turn that pass off, put black velvet on there, light the model and shoot it again against black.

“I didn’t think that was going to work, because the blurred edge of the negative space image wouldn’t be the same as the positive space image. So I said that the only way to do this, was to use bluescreen… There was just no other way to do it. Besides that we had to do a lot of model explosions and stuff like that and you can’t do that with front light – back light.”

“So we developed a bluescreen process. I got Al Miller, who was our electronic genius, to come up with a way to shoot fluorescents with DC. The most efficient way to light the bluescreen was to use fluorescent lights, because it’s very, very blue and it doesn’t have any colors in it. The problem was that fluorescent lights flicker. You can shoot stop-motion, motion control with 1 frame/second exposures, but if you try to shoot anything at sound speed or high speed, you have flickering bluescreen which will give you bad mattes. I had Al Miller come up with a technique to direct current in order so we had a DC fluorescent bluescreen.

“It was huge, like 12 feet high. It was as big as it could be inside the stage we had. Essentially what we wound up with was a 12 x 20-foot bluescreen, which was just a big light box with very high output fluorescent tubes inside, so I could shoot F16 or F22 at high speed in front of this bluescreen. I had neutral density filters that I could pull down, which were rolled up inside.

“It was a really nice system and it was on wheels so we could move it around on the set. We had only a 42-foot track and the boom was capable of moving up and down about 8 feet — 4-5 feet up and 4-5 feet down. It had a traverse action and a rotating action. You could do any kind of move with the camera, since the camera could pan, tilt and roll around the nodal point — the entrance pupil of the lens. You put the entrance pupil of the lens in the middle of the pan and tilt – otherwise the camera would appear to sweep across something as opposed to pan across it.

“All of these things were worked out and it took about nine months before we were even able to shoot any film.”

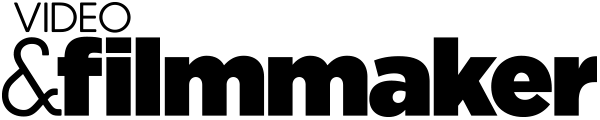

Senior VFX Supervisor and ILM Creative Director, Dennis Muren (pictured above) said in a 1986 interview with Star Wars Insider, that there was so much VFX work to do on Return of the Jedi that it had to be split into three sections.

“I did most of the land stuff and the forests, and I think a few other things. Richard Edlund did the desert stuff and also I think the big final attack on the Death Star, and Ken Ralston did most of the other big space scene sequences.

“The stuff I did, also, was stop-motion. There was stop-motion here and there. That just meant we could each be focusing on a smaller number of shots. I mean, it was a huge show, shot-wise, and it just made sense that you could focus more on each shot and make it better if you weren’t dealing with too many shots.”

“The Empire Strikes Back was the hardest film I’ve ever worked on. We had to train people to do work that we barely knew how to do.”

ILM’s Chief Creative Officer, Senior VFX Supervisor and story-writer of Rogue One: A Star Wars Story, John Knoll said,

“If you were a new guy at ILM, they put you on the night crew—my shift was from 7 pm to about 5 am.

“In my free time I was working on an idea with my older brother, a software engineer getting his doctorate at the University of Michigan. Ultimately it developed into Photoshop.”

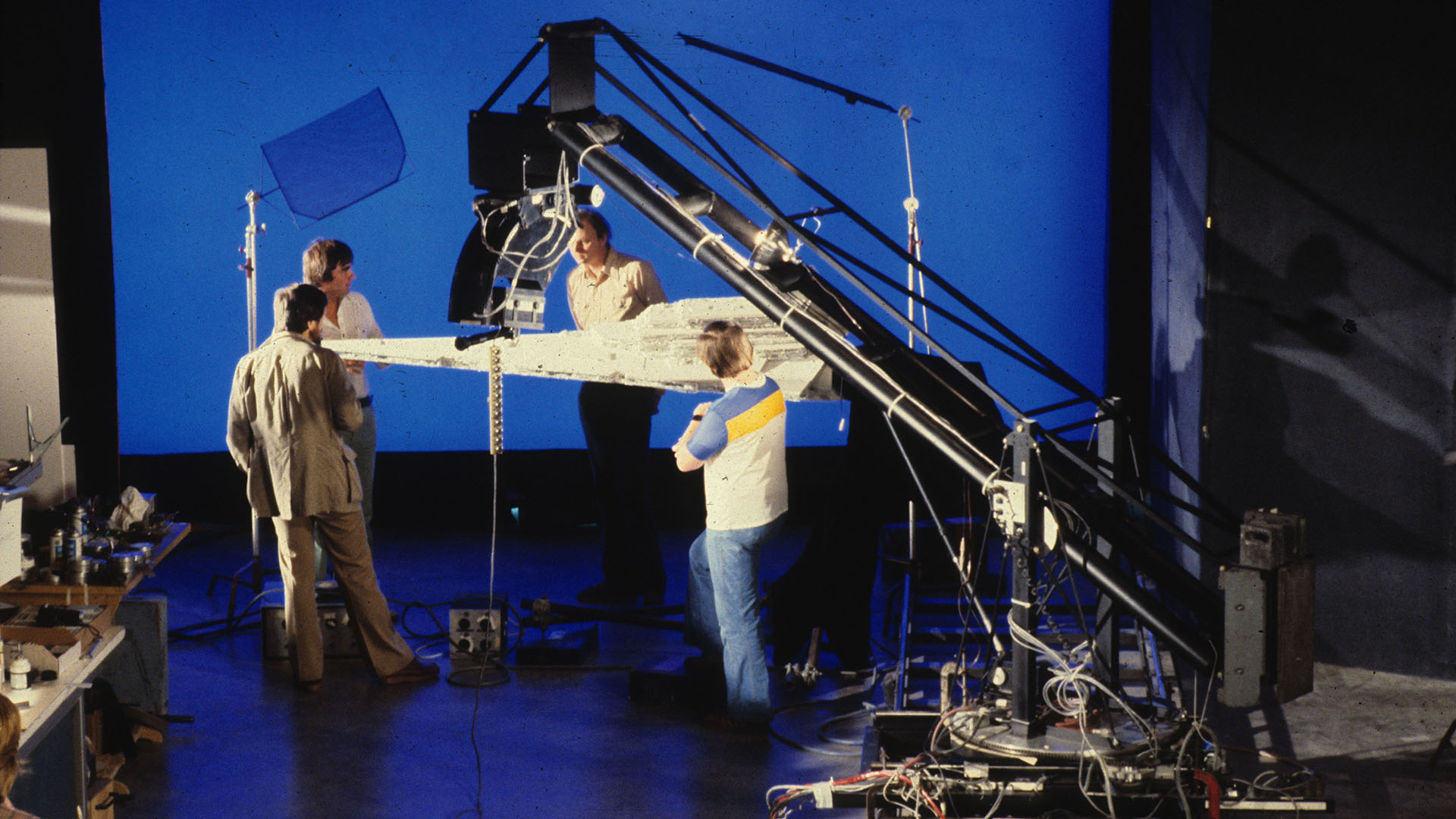

Muren described working on Return of the Jedi as a gargantuan task,

“It seemed huge, and there were a lot of problems that needed to be figured out. I remember we did location scouts up to the redwoods [forests in Northern California]. That was for a lot of stuff — the speeder bike chase, the battle, and the walking machines, stuff like that. I went over to England two or three times, but very briefly.

“So from then on, from my point of view, it was like, “How are we going to do these shots?” I know the bike chase had 100 [effects] shots on its own, and I probably had another 200 or 300 shots. It was a pretty big show, and we kept enlarging ILM. Everything was limited to how much room we had, and yet there was so much work that we had to do things based on camera availability and crew between the three units” (Star Wars Insider).

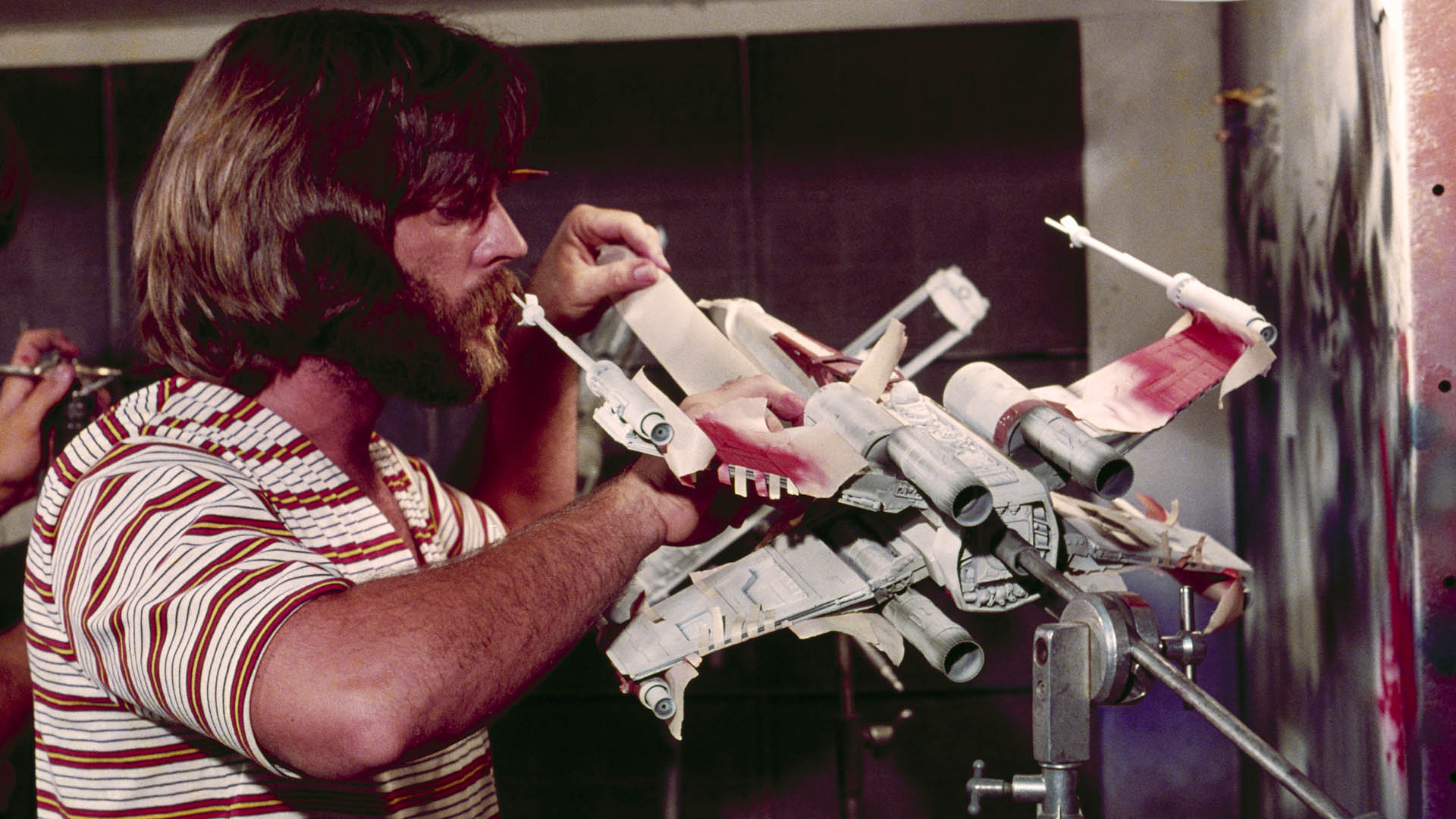

The miniatures created for the films were often made out of the broken pieces of other model kits, a technique known as ‘kitbashing’. Douglas Trumbull used kitbashing whilst working on Kubrick’s 2001, but Brian Johnson (The Empire Strikes Back) had begun using the technique long before on Space 1999,

He told Space1999.org, “Derek [Meddings, FX designer] and I certainly did use plastic kittery in large quantities and I am sure Douglas [Trumbull] used kit parts before 2001.

“I went to the Worlds Toy Fair at Nuremberg and met German kit makers Faller and Volmer and persuaded them to let me pick out the specific injection moulding machines that were doing Girder Bridge parts, etc. and Fuel Tanks, etc. and just let the boxes fill up with the bits we needed. They were so helpful. It saved us thousands on buying one particular kit with hundreds of bits to extract one precious item.

“Nowadays, we get the parts and then mould our own versions, using rigid fine grade polystyrene foam so the finished result is as we want, but light in weight as well, quite a consideration if large areas have to be covered. If I had clad Nostromo using the later technique, it would have weighed far less.”

Discussing those early model making days on Star Wars, Lorne Peterson said,

“It’s hard to imagine a world without superglue, but in the early 70s it was a pretty rare item. It was an industrial product.

“I was originally hired as a modelmaker for two months, at the end of ’75, just to do one particular project. When I went there, every day, I realized, my god: I was involved with industrial design, so I knew about super glue, but they’d use five-minute epoxy with masking tape to do [Princess Leia’s] ship. That’s the way they were doing it. I knew that there were other ways to do it.

“Usually we build more interior than you’d originally think, for explosions, just in the possibility, in anticipation that something might show. Many times it doesn’t, the explosion covers it. An example of that is when the Ewoks crush the head of the chicken walker with the logs.

We actually made two characters with helmets and all that kind of stuff and a little light inside. We sculpted one to look like George Lucas and one to look like the director of the film. They actually looked like them, because they were about 16 inches tall. The heads got crushed and you never saw them. Most of the time it wasn’t necessary, but every once in awhile we did at least a partial interior,” (Tested.com).

However, once CG began to take centerstage, the world of miniature model creation and practical effects almost became a lost art.

As Charlie Bailey and Phil Tippet, key ILM modelmakers describe,

“When the CG started up, we all panicked. It was like, “Oh my God, these guys can put us out of business in about a year” Bailey said.

“It was catastrophic for me. All my skill and craft was thrown out the window. There was no way I was going to work on a computer” Tippet replied. “That necessitated bumping me upstairs, operating more in an animation supervisory capacity.”

“[It] generated so much more interest in special effects that we got even more work,” Bailey said (Wired).

Want More?

Check out our articles Bringing Star Wars Down to Earth and our piece on the art of miniatures & practical effects, If You Build It Will the Audience Come?

All images courtesy of LucasFilm and ILM.