The use of practical effects is a somewhat lost art in traditional filmmaking these days. Computer rendered effects are often far cheaper to source and don’t require set or crew time. But does the technological advancement in visual effects and its prolific use in cinema, come with a cost to the magic of movies?

By Nicole Boyd

Practical effects, or more precisely the use of miniature models in filmmaking goes all the way back to the era of silent films. One of cinema’s first films to incorporate miniature sets and models to its storytelling was Georges Méliès, in his iconic 1902 film Le Voyage dans la Lune.

Since that time, the use of miniatures or scaled sets has gone from being extensively used, largely for for exterior shots, to rarely used at all. Superseded by CGI.

Iconic scene from Le Voyage dans la Lune (image: public domain).

But, who can forget the opening scene of Tim Burton’s Beetlejuice? The camera flying above a meticulously made model township, the model itself later featuring in the film.

Or the viking ship battle scene in Cecil B. DeMille’s Ben Hur.

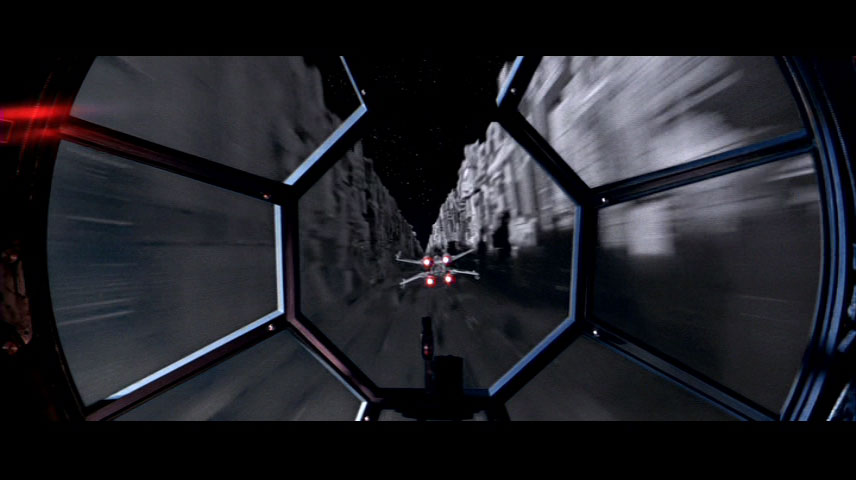

Or even Luke Skywalker as he blows up the Death Star, with R2D2 flying shotgun in the X-Wing and Vader hot on his exhaust trail.

The practical effects are strong with this one.

It’s just not the same using CGI. Although some may say it’s better, and yes, it definitely is better in some respects. But at times, it feels like we’ve lost the grandeur of cinema.

A great example of this is seen in the exterior shots in Baz Luhrmann’s recent remake of The Great Gatsby. The film was the crowning achievement for many hard working compositors, our friends from Australian VFX house Animal Logic, included.

It’s visually beautiful, but have audiences become somewhat jaded? Is the grandeur of a set created largely in CGI and then composited in via green screens, less grand?

As Luhrmann pointed out when discussing the VFX and sets of his other great spectacle Moulin Rouge (source):

“We live in a world where audiences are not only aware but profoundly bored of the perfection of digital magic. Cameras move perfectly at impossible angles, reality has a beyond-real sharpness.”

Luhrmann and his Production Designer wife, Catherine Martin, commissioned VFX Supervisor Chris Godfrey and the team at Animal Logic to reproduce film errors and aberrations in the effects.

Saying, “We wanted to use digital power not to create perfection but imperfection, to reproduce camera shake, deconstruct imagery and create a sense that this film was hand made.”

Exterior set of the Grand Budapest Hotel. The model itself is 4.2 meters long (14 feet) and 2.1 metres (7 feet) wide (image: courtesy of Fox Searchlight Pictures).

Likewise, when working on The Grand Budapest Hotel, director Wes Anderson was fully aware of audience’s understanding of the artificial in filmmaking.

Taking that artificial up a notch, Anderson embraced the old world filmmaking style of practical effects, by incorporating miniature models and matte painted backgrounds for the film’s exterior sets. Telling the New York Times, “I’ve always loved miniatures in general. I just like the charm of them.”

Also stating, “The particular brand of artificiality that I like to use is an old-fashioned one.”

Anderson collaborated with production designer Adam Stockhausen to create a number of set models for the film. The hotel’s design looked like a “greatest hits of various forms of inspiration”, an amalgamation of European architecture, the US Library of Congress and the Grandhotel Pupp in the Czech Republic.

The Grand Budapest Hotel’s design sketch by Carl Sprague (image: courtesy of Fox Searchlight Pictures).

The models were built at Studio Babelsberg in Potsdam, whilst principal photography was taking place at Görlitz, Germany.

The hotel and its funicular railway were built separately and then composited together in post This was done to ensure the smaller details looked realistic.

“When you’re carving the rock of this hillside, you can only go so small before you start to lose the detail and it won’t look real,” Stockhausen said.

Model makers working on the hotel sets (image: courtesy of Fox Searchlight Pictures).

Accompanying the models were matte painted backgrounds, created by Michael Lenz, in the style of 19th-century landscape artist Caspar David Friedrich.

The paintings were keyed in during post, giving the exterior shots an airy, romanticised aesthetic, that sits well within the memories of the film’s protagonist concierge Gustave (played by Ralph Fiennes). Adding to the fantasy artificiality Anderson was looking for.

“As a painting, it created a filtered way of looking at the world,” Stockhausen said.

Exterior set of the Grand Budapest Hotel (image: courtesy of Fox Searchlight Pictures).

The miniatures were then shot on Red cameras, with three different aspect ratios and in post were combined with computer generated effects. Much of this work was undertaken by VFX house LOOK Effects.

When discussing the shots, LOOK’s Visual Supervisor Gabriel Sanchez, told CGSociety,

“We were provided with a miniature of the hotel and had to rebuild it digitally. Not a complex job on the surface with the hotel really just being architectural geometry however it rapidly became obvious that the lighting and the mattes would need to integrate seamlessly with the model to make it really work, and this is where the team really proved itself.” says Gabriel.

“We got together and, thinking outside of the box, worked out how we would do it. We determined that concentrating on how the shadows would expand and move across the building would create the magic. This to me really showed the team working well, as the shot came together not because of the modelling, or the matte painting, or the compositing, but the whole combination working together to create something that really ‘popped’.”

Showing us that even practical effects need a little CGI help from time to time.

So, what do you think? Has cinema lost some of its magic using computer generated sets? Or is the artificial reality of filmmaking more believable now?

Let us know your thoughts by commenting below, or on our Facebook, or Twitter pages.. We’d love to hear your thoughts.

The observatory model (image: courtesy of Fox Searchlight Pictures).

Watch the BTS featurette, on the creation of The Grand Budapest Hotel set below.

Sagar R. Agrawal

And that’s what i called is “Creativity n Hard Work”…