A pair of Aussie filmmakers have just released the world’s first feature-length documentary shot entirely in near-infrared – a spectrum of light beyond what the human eye can see.

Article by Nicole Boyd

BRINDABELLAS | edge of light – is an immersive 140-minute cinematic journey (broken into 22 bite-sized chapters) through the sky and mountainous region surrounding Australia’s capital city Canberra.

The film focuses on the interplay of mountain light, air, water and the elements, and the transformation of each as they progress throughout the seasons.

Exploring both the wide mountain vistas of the Brindabella Ranges, along with more intimate details of the natural flows that are created by these mountains.

From mist rising up from the ranges, to form the clouds that pour rain, snow and ice over the mountains. Melting in warmer months to fill the many rivers and creeks, which in-turn shapes the very landscape it originated from.

The best part is that all 22-chapters of the film – in all their stunning 4K glory – are free to watch!

Glen Ryan and James van der Moezel, the duo behind Silver Dory Productions, say the film’s release is the final step of a journey that began in 2013.

The two filmmakers modified a number of RED Digital Cinema cameras so they could capture the light from the near-infrared spectrum.

Opting to shoot in near-infrared (instead of far-IR) because they didn’t need to capture the temperature or the electromagnetic radiation visible in the longer wavelengths (which is primarily used for thermal imaging, astronomy, etc.).

The human eye is typically able to see the spectrum of light between wavelengths of 390 – 700 nanometres (nm) whereas (far) IR wavelengths are between 700 – 1,000,000nm (or 1 millimetre). The near-IR spectrum wavelength sits between 750 – 1400nm, so it’s only slightly beyond what the human eye can naturally see.

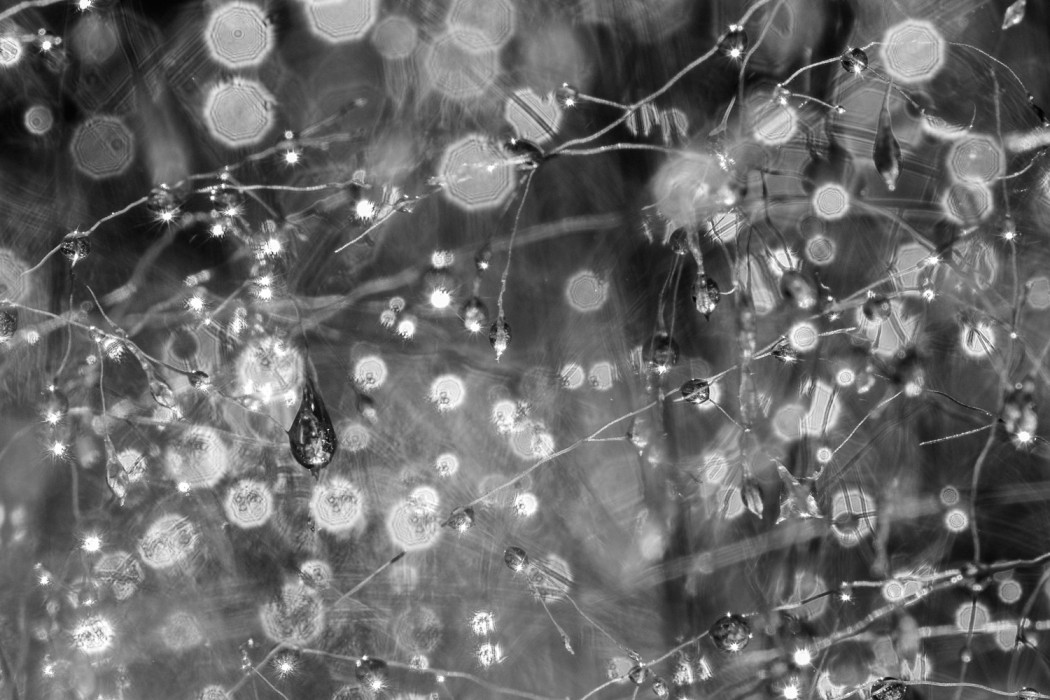

Aesthetically however, it removes (almost) all colour, turning the sky black and skin a milky white (with eyes often completely black). Tree foliage and grass become bright and the reflected blue of the sky seen in clouds and water becomes a dark and moody shadow.

It transforms the things we see in everyday life into surreal objet d’art.

It’s also a hell of a lot less expensive to modify a camera to shoot in near-IR instead of the longer IR spectrum. There’s a lot of digital cameras on the market these days that have a kind of fake IR setting, which is primarily just an in-camera monochrome high-contrast ‘look’. You can also buy IR-pass lens filters that will give you a slight bump to the wavelengths.

However, for Brindabellas, the guys from Silver Dory went straight to RED Digital.

Talking to Video & Filmmaker, James said:

“We originally shot a piece called ‘Karst Country’ down at Wee Jasper [in Australia] on the Scarlet which wasn’t modified but allowed a little bit of IR through.

“It was after that we decided get an EPIC and asked RED if they would modify it for us to allow IR light to hit the sensor unobstructed. They agreed to do that for us by fitting the EPIC with a Full Spectrum OLPF – basically a clear filter – which lets all light through it.

“So now to shoot IR on the EPIC all we need to do is filter the front of the lens with an IR Pass Filter usually starting at 720nm. This also means to shoot colour we need to us an IR Cut filter to fill the role that the original OLPF performed. The release of the RED DRAGON with its interchangeable OLPF system has allowed for more people to try out IR without having a modified camera.”

Glen added:

“Since we shot the film RED have made all this simpler by offering interchangeable OLPFs in their Dragon and Weapon cameras – so to do the same thing now you would simply slot in a full spectrum or IR OLPF – not need for factory modifications anymore.”

Great news for anyone else wishing to use a RED to capture near-IR imagery for their projects.

Glen Ryan trying to stay warm whilst shooting the doco.

Glen Ryan spent two years photographing and shooting the film and when discussing his reasons to shoot in near-infrared said:

“I feel its distinctive look is ideal for capturing the essence of many Australian natural landscapes. There’s also a certain magic in recording images with light you can’t actually see.

“In sunny conditions, near-infrared produces a striking combination of dark skies and water, perfect white clouds and ghostly pale glowing foliage. It also cuts through atmospheric haze and accentuates shadows in a landscape, particularly in the late afternoon or dusk. These bold shadows add an extra dimension to many landscapes.”

“Another aspect that appeals to me is its inherent imperfection – the inevitable grain, flares, aberrations and unforgiving inflexibility. Up close, near-infrared images often resemble a disconcerting chaos of visual noise. But at a reasonable viewing distance, a clear and striking image emerges from the coarse and compromised details.

“To me the flaws of near-infrared make the unique beauty and depth of the final images even more appealing. The work required to tease out this beauty from uninspiring raw files only makes the challenge more rewarding and the final image more satisfying.

“As digital imaging attains new levels of resolution and clarity, I still find that near-infrared’s limitations add to its aesthetic appeal – and its problematic nature only enhances the magic of the completed image,” Glen said.

James van der Moezel capturing the effects of the changing season on the landscape.

James van der Moezel, head of post-production at Silver Dory, said that one of the main challenges he found whilst working on the project was finding a way to deliver an unconventional film to a wide-range of audiences.

“We were always looking to create something more substantial than the short infrared motion pieces we had ‘tested’ previously. But we also realised that two hours of black and white landscape art might not work for everyone – so we set out to develop a film which could be broken down into smaller sections for different audiences watching it on different platforms.

“By releasing it as 22 chapters the film can now be enjoyed in short grabs or combined into longer seasonal narratives – or the complete two hour experience,” James said.

Glen says the film is not only about visiting an ‘exotic’ mountain range, but also exploring at length the everyday back-drop of a capital city.

“While [the documentary] features some beautiful wilderness and natural ecosystems, most of it was actually filmed from within the suburbs of Canberra, the capital city of Australia! The most remote location featured is still less than an hour’s drive from the centre of the city – a lot of the footage was simply shot from the side of suburban roads.

“The ambiguity of exactly where the edge of the city transforms into the edge of the wilderness is what made Canberra the perfect setting for this project.

“The unique ability of infrared imagery to capture the interactions between land and cloudscapes allowed us to explore these familiar settings in a more surreal way than a traditional documentary – and hopefully now reveal them to a wider audience in a new light,” he said.

The documentary BRINDABELLAS | edge of light is now available to view (all 22 chapters – for free) at : brindabellas.com.au

All images and quotes courtesy of Silver Dory Productions.