The last 15 years of has seen some dramatic changes in audio production and even more with sound in post. Despite the love of retro gear by music engineers, the same cannot be said for editing film sound – the heart of which is now the computer DAWs and plugins.

Story by Brent Heber

RETURN TO FADERS

Many will remember the Fairlight MFX or dSP Postation (both Australian innovations) with great affection. Digidesign’s ProTools MixPlus system effectively buried those post-specific hardware/software solutions. Mixing in the box became de rigueur — a consumer computer is now commonly the heart of our professional audio world, with enough grunt to mix and process hundreds of tracks with stunning clarity.

Ironically, not so long after convincing the industry it didn’t need faders, Avid née Digidesign set about selling faders back to post studios, releasing the ProControl, Control24 and, most notably, the Icon surfaces in 2004. All this in 15 years.

Icon has been widely adopted, with Avid’s latest Eucon-based System 6 the latest innovation.

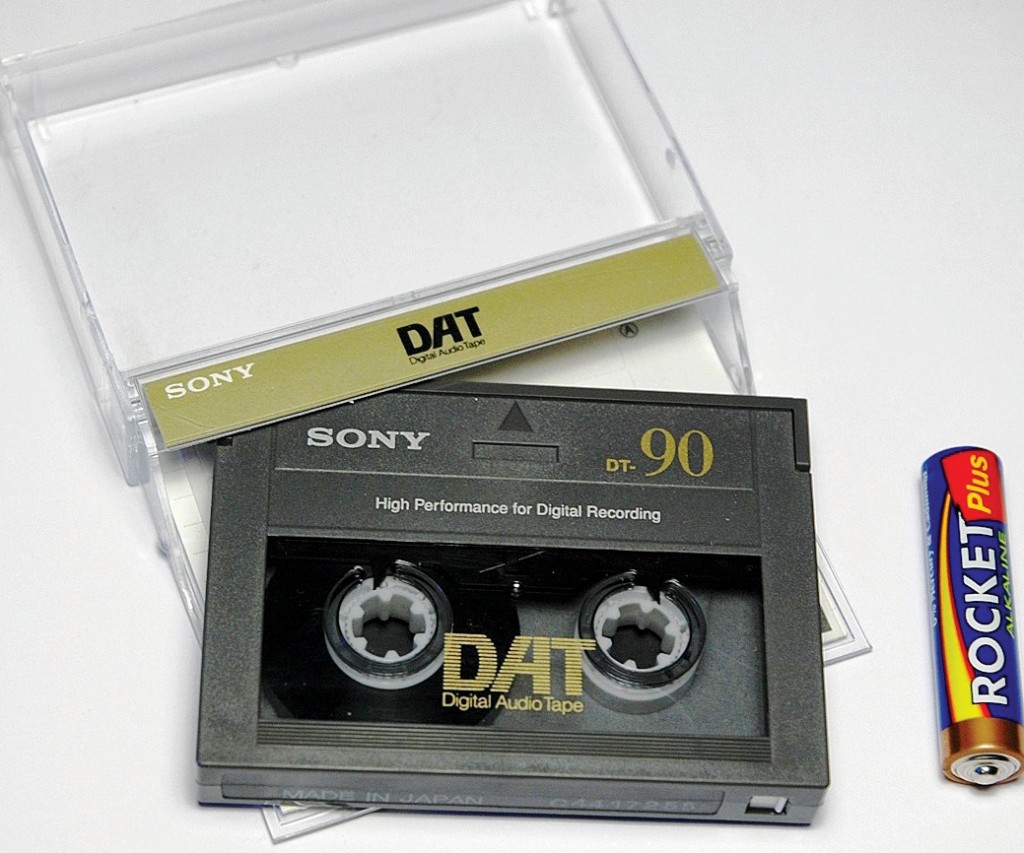

DAT Cartridge

MANY DEATHS OF TAPE

Timecode and the various niche machines that read it and acted on it were vital for post production 15 years ago. Sony announced the end of its DAT machine production in 2005 and most soon followed, allowing hard drive-based sound recorders to flourish. Now, a location sound recordist might hand over a USB stick, a hard drive or a DVD-RAM disk full of Broadcast Wave Files. Smooth sailing from hereon? Not quite. Even though DAT replacements have been around for years, most video software to this day have a bunch of gotchas about how they deal with location sound files, and film productions are still rife with workflow problems trying to get audio in sync in this new digital age.

Working in Dolby ATMOS (Soundfirm)

QUICKTIME IN NICK OF TIME

Early days in the new millennium, an audio post house would be routinely sent video on tape, Betacam, SP, digital, you name it. Some of these decks cost upwards of $70k, so the ‘price of admission’ kept novices out of the industry. Although QuickTime movies existed back then, the common trend was to plug in the tape and capture the images, convert that into a QuickTime movie, spot it into your workstation and start working. These days, we’re skipping the middle man and the picture editor exports all manner of video files for different people depending on their craft: the composer will get one, the audio post guys, the colour graders and all these 1s and 0s then go to air, often submitted to broadcast now as a digital file.

Home Studio (picture by EelkeKleijn )

WORKING REMOTELY

Faster, cheaper internet as meant the wide-scale adoption of file sharing sites like Dropbox and Yousendit. While ISDN became a thing of the past for remote voiceovers and ADR. Source Connect was the final nail in the coffin and we could now start recording at decent quality from DAW-to-DAW over the web. Timecode lockup was added, dropout capturing/buffering was added and now it’s commonplace to record someone on the other side of the world using this sort of technology. The post pro world has shrunk considerably as a result and many freelancers are taking on work from home without the overheads of bricks and mortar.

Dolby ATMOS mixing desk

OPEN SOURCE SOUNDTRACK ENCODING

Since 1976, Dolby Stereo and its later surround incarnations have ruled the cinema sound roost. The whole point of Dolby Stereo was quality control at both ends: noise reduction and encoding to put the soundtrack onto the sprocketed film, and then decoding hardware to read it and play it back in the cinema. In a masterstroke, Dolby only <licensed> the encoding devices to dub stages, and sent out a technician to operate it. So if you wanted to finish a project on film, you needed to pay Dolby for this service and we’re talking five figures.

George Lucas emerged as an unlikely saviour. He chose to demonstrate a new digital format for cinema called the Digital Cinema Package (or DCP) by releasing <Episode 1 The Phantom Menace> on this format, played digitally in four cinemas in the USA. DCP was originally developed as a package to distribute films digitally but the Society of Motion Picture & Television Engineers (SMPTE) saw its full potential. A DCP contains MXF media, with JPEG2000-encoded video and BWAV mono audio, 24-bit/48k. That’s right, the audio in the DCP is just uncompressed wav files — no more expensive Dolby licenses and equipment hire, any ol’ bedroom cowboy can now make a film soundtrack. That’s right, the democratisation of film sound hasn’t been without its land mines. Interestingly, Dolby is doing its best to reinstate the old status quo with the introduction of Atmos.

LOUDNESS: PEACE AT LAST

A lot of research has been done into how the human ear perceives the loudness of an audio signal and once that was understood a dBFS-scale measurement was developed representing a far superior way of working than using RMS or peak scales; something more closely aligned with human hearing. The key difference is that loudness is measured over time: an ‘integration time’. Consequently you can have instantaneous measurement of loudness, short-term measurement (over say 2-5s) and then ‘integrated’ over the duration of your program material.

Along the way, our headroom in the final product is also changing. For analogue transmission we always had to keep our audio below -10dBFS. With the digital age we can now open up those limiters all the way to -2dBFS, however this is measured as a ‘true peak’ or integrated peak, ie. how high the peak would really be in the analogue realm if the digital signal were put back together again. We can now mix a lot more dynamically for TV, aligning more closely with the cinema mixing experience.

![DolbyAtmos_[Print]2](http://videoandfilmmaker.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/DolbyAtmos_Print2-1024x576.jpg)

Feature Image: Dolphin Digital Productions main studio’s TAC Scorpion 30x8x2 Mixer (image: ©Dolphin Digital Productions, New Jersey).