Getting the Most out of Working with – or Without – a Composer

By Robert Clark

James Horner had a public spat with Terrence Malick after The New World, Carter Burwell dropped out of Thor: The Dark World due to “creative differences”, Mark Mothersbaugh destroyed expensive instruments in a rage after a scoring session on Cloudy With A Chance of Meatballs. Okay, that last example is a (hilarious) spoof, but it’s clear that relationships between composers and directors often end in tears. It’s not always about a clash of egos, either – sometimes both parties approach a project with different expectations, and conflicting ideas about how to collaborate. If you’re keen to avoid having a heated falling-out with your composer, the best plan is to think about what kind of collaboration works best for you and – dare I say it – if you need a composer at all. Here are some options that may help.

From the Script Level

Bringing in a composer for a ‘spotting session’ at the script level is ambitious and perhaps a little idealistic given how much films tend to change between script and screen. Having said that, this type of collaborative relationship can work very well. Composers Johnny Klimek and Reinhold Heil along with director Tom Tykwer (think Run Lola Run) work this way, and M Night Shyamalan’s partnership with James Newton Howard is another example. A composer will likely shower you with praise for this sort of freedom, but will still have to cede control once the film is cut because it’ll be up to you to make the music fit. This is why Peter Greenaway and Michael Nyman severed ties after a 24-year partnership; Greenaway took so much licence with the score in Prospero’s Books, Nyman couldn’t take it any more and called a permanent end to their collaborations.

After the Lock-Off

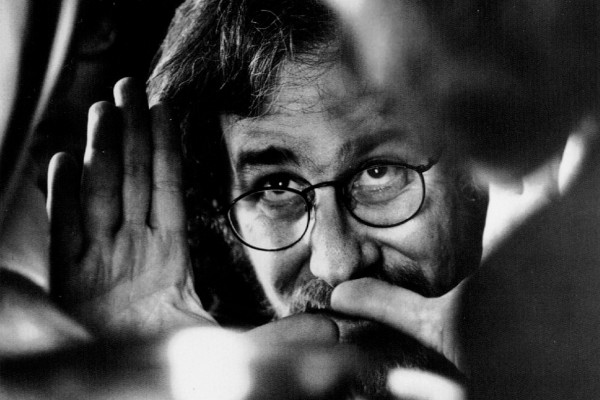

Another option is to sit down with your composer once you have a locked-off cut, with only dialogue and minimal effects in the audio track. You can pause the film as you go and discuss options for music at key points, and even whether music is needed at all. In this scenario, both of your opinions about the nature and application of music are considered equally, which makes this an ideal situation from the composer’s point of view. And there are many examples of this type of relationship working well. Steven Spielberg and John Williams – arguably the most successful composer/director duo ever – work this way (although there is the famous instance of Spielberg deciding to re-cut the finale of E.T. to Williams’ score, which Williams admitted was “extremely rare”).

And by the way, the reason I’m saying ‘lock-off’ instead of ‘fine-cut’ or ‘rough-cut’ is that once a composer starts writing music to scenes in your film, it can be incredibly tricky and time-consuming to adjust that music to new cuts. So although it may mean holding off your spotting session a bit longer, you’ll save time in the long run by waiting until you’ve achieved picture-lock.

Collaborating to a Temp Score

This is often considered the best method of collaborating from a director’s point of view because it helps to communicate very clearly what you want from the score. If you consider yourself musically illiterate, you may well consider this your best option. It means spending a lot of time sifting through your music library and those of your friends but once you’ve settled on what you believe works best, you’ll have a ‘temp score’ that you can send to your composer to use as a template.

This method has its downsides, though. There is a very real thing called ‘temp love’ (trust me; it’s a thing). Basically it refers to situations where the director has heard a piece of music so often in the edit they become wedded to it emotionally, and nothing the composer writes can live up to it. This happened to composer Jerry Goldsmith on Alien, although the temp music the director and producers fell in love with was the composer’s own music from a previous film. Jerry Goldsmith: “There’s the scene where the pods open, where they wake from hyper sleep, and which they’d temp-tracked with some of my music from [the 1962 film] Freud. They all said, ‘Isn’t it wonderful?’ And I said, ‘No, it’s terrible. It doesn’t work at all.’ I wrote something that was really wonderful for that scene and they ended up buying in the music from Freud. They fell in love with the temp music.”

M Night Shyamalan and James Newton Howard – the pair have collaborated on many of Shyamalan’s films.

See? It’s a thing.

So there are benefits in terms of clarity of communication, but it’s less collaborative and there are many examples of composers and directors coming to blows as a result of ‘temp love’. So if you go down this path, remember: your temp score is only a guide and will have to be discarded eventually.

Royalty-Free Library/Production Music

As composer I’m admitting this through clenched teeth, but nowadays library music is extremely well produced and affordable. Websites such as BigBang&Fuzz and AudioNetwork offer an almost bewildering array of music that can be downloaded as individual tracks or as albums of a particular theme such as ‘Epic’ or ‘Dreamscapes’. YouTube has also just launched a new feature called AudioLibrary, which offers quite a wide array of tracks (of varying quality) available for free download (EDT: check our Free Stuff section for more royalty free music options).

A lot of this music is loop-based, which means it’s intentionally composed in blocks that can be lifted from the track and looped, or can be easily chopped at different spots without sounding weird. However, what you gain in ease of use and thrift, you lose in originality and flexibility. It’s worth remembering that once you download a track and use it in your film, it’s not taken off the site; anyone else can buy it and use it in their film too. And although a lot of it is loop-based, there’s still a limit to how much you can do with the tracks to make them hit your important cue points. Of course, not all directors worry about this. Quentin Tarantino is a great example of a writer/director who almost always uses pre-existing music of wildly different styles and makes it work brilliantly.

Who Needs Music Anyway?

An excellent starting point for a director when thinking about music is to ask: do I need it? This forces you to think critically about what music will add, or indeed subtract, from your film. Watch your film from start to finish and think about what effect a score will have. Will adding music change it? If you decide music is necessary, what exactly do you need it to do?

It’s easy enough to find examples of directors who have asked those questions, decided against music altogether, and still made a great film. Hitchcock’s The Birds and Lumet’s Dog Day Afternoon are oft-cited and excellent examples. Cloverfield worked very well without a score, as did Cast Away. (I wonder what the rationale was for that, by the way. I’m reminded of when the composer on Hitchcock’s film Lifeboat was told his music had been scrapped because the director wasn’t sure where the music would come from in a film set in the middle of the ocean. The composer replied, “Ask Mr Hitchcock to explain where the camera came from, and I’ll tell him where the music comes from”).

While existential questions about music’s presence in the medium of cinema is possibly a path to madness, a more practical question relates to the emotional and diegetic implications of silence. Think of how well silence was used in No Country For Old Men, for example. Sometimes nothing at all can be so much more powerful than a 100-piece orchestra.

In reality, films are often made by combining these methods. At the end of the day, if you decide to hire a composer, then clear communication is key. Sit down and have a chat about the best way to work, and approach the process with an open mind and an adventurous spirit. After all, once you and your composer understand each other’s process and style, your collaborations will become easy and most importantly, highly effective.