Multiple Oscar winning film editor & sound designer Walter Murch‘s distinguished 50-year career reads like a ‘best of’ list of feature films. His work as both editor and sound designer on classic films such as Apocalypse Now, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, Ghost, The Godfather II & III, The English Patient and the Talented Mr Ripley mean his word is virtually gospel when it comes to filmmaking.

Written by Nicole Boyd

Along with all his work behind the big screen, Murch has been the subject of numerous books and documentaries over the years and was also the first filmmaker awarded an Academy Award for editing on a digital system (Avid).

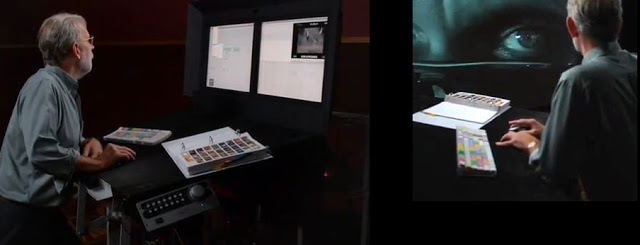

Not one to rest on his laurels however, he is slated to edit Disney’s next animated classic Tomorrowland and he also spends time mentoring with the Rolex Mentors & Protégés program (pictured above with protégé Sara Fgaier).

Murch working with his FCP set-up

Within Murch’s book In the blink of an eye: A perspective on film editing he discusses something he calls the ‘Rule of Six‘.

Six elements to building the story within the edit, which he describes as a list of priorities:

“What I’m suggesting is a list of priorities. If you have to give up something, don’t ever give up emotion before story. Don’t give up story before rhythm, don’t give up rhythm before eye-trace, don’t give up eye-trace before planarity, and don’t give up planarity before spatial continuity.” (i)

These priorities can be used as a formative plan for your edit or a guideline to follow that ensures your edit keeps your audience invested in the film.

“The ideal cut is one that satisfies all the following six criteria at once.”

Walter Murch working on the sound design of ‘Apocalype Now’.

1. Emotion

How will this cut affect the audience emotionally at this particular moment in the film?

Telling the emotion of the story is the single most important part when it comes to editing. When we make a cut we need to consider if that edit is true to the emotion of the story.

Ask yourself does this cut add to that emotion or subtract from it?

It is important to consider if the cut is distracting the audience from the emotion of the story, Murch believes that emotion “is the thing that you should try to preserve at all costs”,

“How do you want the audience to feel? If they are feeling what you want them to feel all the way through the film, you’ve done about as much as you can ever do. What they finally remember is not the editing, not the camerawork, not the performances, not even the story—it’s how they felt.” (i)

Murch working in FCP

2. Story

Does the edit move the story forward in a meaningful way?

Each cut you make needs to advance the story. Don’t let the edit become bogged in subplot (if it isn’t essential) if the scene isn’t advancing the story, cut it.

Remember what Faulkner says “Kill all your darlings” (yes, he’s talking about writing but it’s also true in filmmaking).

If the story isn’t advancing, its confusing or worse – boring your audience.

Walter Murch speaking at Sundance

3. Rhythm

Is the cut at a point that makes rhythmic sense?

Like music, editing must have a beat, a rhythm to it. Timing is everything.

“it occurs at a moment that is rhythmically interesting and ‘right'”

If the rhythm is off, your edit will look sloppy, a bad cut can be ‘jarring’ to an audience. Try to keep the cut tight and interesting.

These top three – emotion, story, rhythm – are essential to get right.

“Now, in practice, you will find that those top three things on the list…are extremely tightly connected. The forces that bind them together are like the bonds between the protons and neutrons in the nucleus of the atom. Those are, by far, the tightest bonds, and the forces connecting the lower three grow progressively weaker as you go down the list.”

4. Eye Trace

How does the cut affect the location and movement of the audience’s focus in that particular film?

You should always be aware of where in the frame you want your audience to look, and cut accordingly. Match the movement from one side of the screen to the other, or for a transition, matching the frame, shape or symbol, e.g. Murch when editing Apocalypse Now uses the repetition of symbol, from a rotating ceiling fan to helicopters.

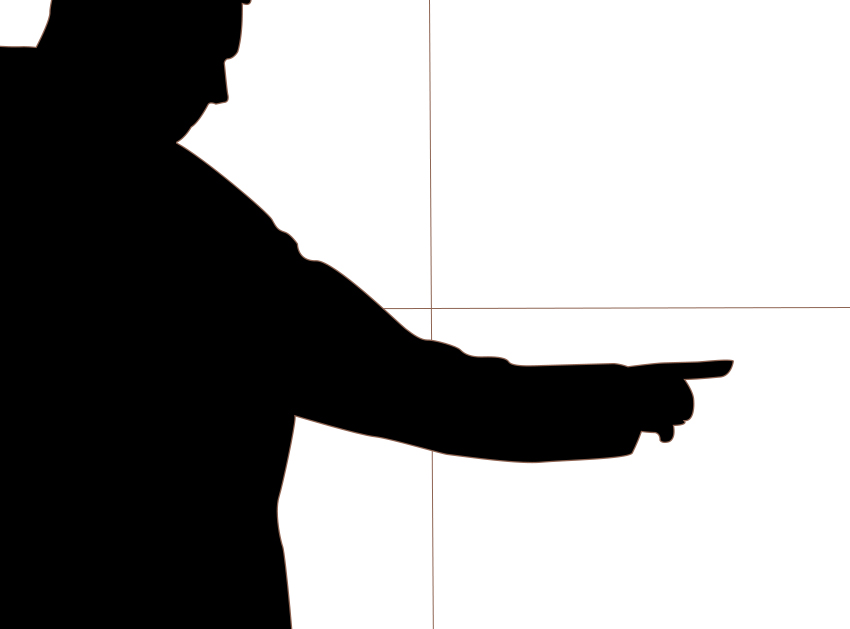

Break the screen into four quadrants, and try to keep the movement in one of those quadrants. For instance, if your character is reaching from the top left quadrant, and his eyes are focused to the right lower quadrant that is where your audience’s focus will naturally move after the cut.

Remember to edit on the movement

and match the action

Remember to edit on movement and to match the action, keeping the continuity as close as possible.

5. Two Dimensional Place of Screen

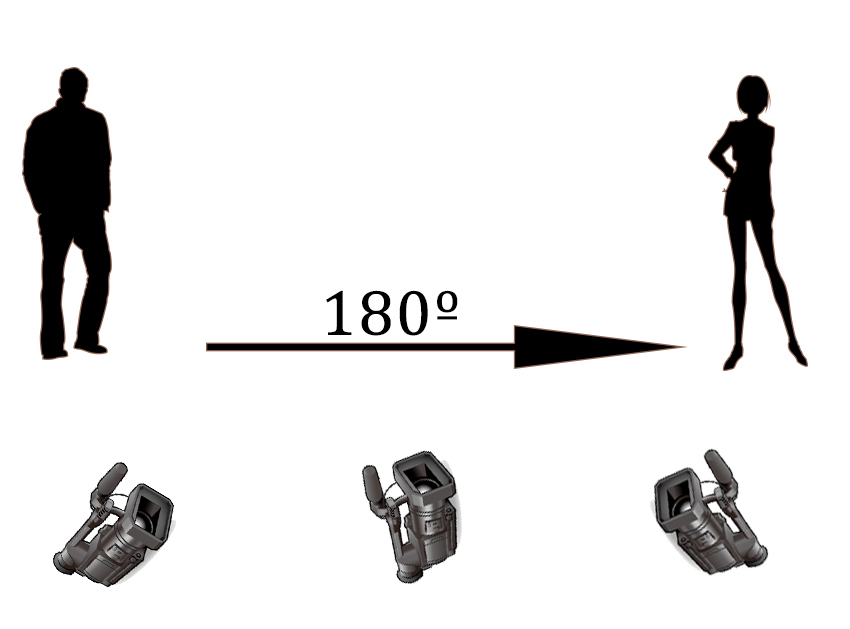

Is the axis followed properly?

Make sure your cuts follow the axis (180º line). This will keep the action along it’s correct path of motion and maintain the continuity. Looking at your quadrants again, be sure the movement flows along the same path, for example a car leaving the left side of frame, would enter again via the right. Sticking to the 180º line (I’ll explain this more below) allows the audience to keep track of the spatial place of characters and objects in your film.

Using a reverse-angle in the preceding shot would be disconcerting to the audience, due to crossing the 180º line

6. Three Dimensional Space

Is the cut true to established physical and spacial relationships?

During shooting the 180º rule states that you draw an imaginary in between your characters and keep the camera on just one side of that line, this is true for editing also.

This rule should always be adhered to, unless you purposely break it. Breaking the 180º line works really well if you want your audience feeling confused, or to disorientate them.

A great example of which is Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, scattered throughout are reverse-angle wide shots between characters, the freezer door opens from both sides of frame (from one cut to the next), even the architecture of the set makes no sense with doorways to rooms that spatially would be somewhere mid-air above stair ways. The managers office (where Jack is interviewed) has a window with a view to outside despite being located in the middle of the hotel/set.

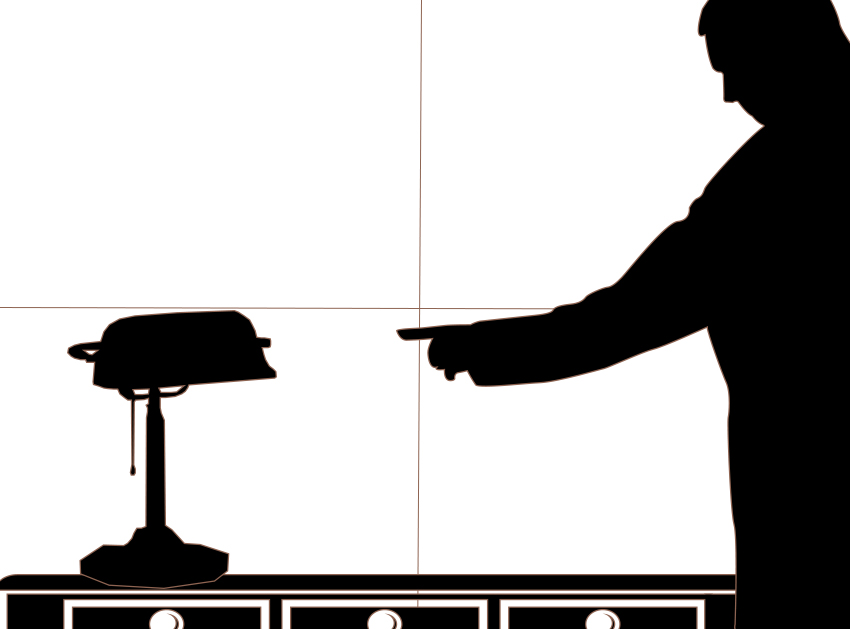

Kubrick crossed the 180º line many times through out ‘The Shining’ (image: courtesy of Warner Brothers).

The point is, stick to the 180º rule, and spatially your edit will work, unless you really want to mess with your audience’s minds

Murch likes to edit standing up (image: copyright Rolex)

Murch states that above all else emotion is the most vital element, beyond that the top three should really be at the forefront of the edit. He even assigned values to each rule and its relevant importance.

“The values I put after each item are slightly tongue-in-cheek,” he writes, “but not completely: Notice that the top two on the list (emotion and story) are worth far more than the bottom four (rhythm, eye-trace, planarity, spatial continuity, and when you come right down to it, under most circumstances, the top of the list—emotion—is worth more than all five of the things underneath it.”

“If you find you have to sacrifice [any one] certain of those six things to make a cut, sacrifice your way up, item by item, from the bottom.” (i)

1. Emotion (51%)

2. Story (23%)

3. Rhythm (10%)

4. Eye Trace (7%)

5. 2D Place of Screen (5%)

6. 3D Space (4%)

For more on Walter Murch and his editing techniques, watch these two important videos.

The first is a short video of Murch explaining the ‘Rule of Six’ in his own words and the second is his masterclass where he discusses his body of work, from editing on the Steenbeck to the latest technical advancements in film editing and “examine the salient technical, artistic, and philosophical differences between the post-production of a theatrical scripted film and a feature-length documentary”.

They’re a great chance to listen to a master filmmaker discussing his art.

Refs:

(i) Murch, W. In the blink of an eye: A perspective on film editing. Silman-James Press, 1995

The Craft: Walter Murch, article Hero Magazine

Walter Murch’s Simple Approach to the rule of six , article, masteringfilm.com

The Rule of six Walter Murch, blog, berkly.edu

Walter_Murch_and_Sara_Fgaier: a_year_of_mentoring, article, rolexmentoringprotoge.com

10000 hours: Walter Murch, article, port-magazine.com

Charles O. Slavens

I’m reading “In The Blink of an Eye”. Can anyone tell me how many cuts/transitions in Apocalypses II? I’m referring to page 3 where this discussion is taking place.

Thanks.